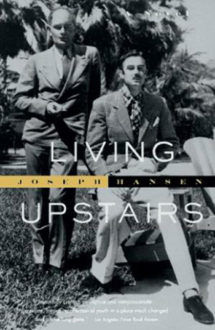

Jack of Hearts / Living Upstairs

Jack of Hearts / Living Upstairs

by Joseph Hansen

Published by Dutton

Living Upstairs published September 1, 1993. 224 pp.

Find on Amazon • WorldCat

Jack of Hearts published January 1, 1995. 224 p.

Find on Amazon • WorldCat

Fiction (mystery)

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

January 1, 2018.

The last book I read in 2017, Joseph Hansen’s Jack of Hearts, the 1995 prequel to Living Upstairs (1993), set two years earlier (in 1941), was disappointing. Living Upstairs was overstuffed with characters and episodes, Jack of Hearts even more so. The protagonist is ultra-handsome Nathan Reed at 17. Over the course of the book that includes mutual masturbation with a waitress, Nathan accepts that he is excited only by other males (including a former partner in mutual masturbation, Gene Woodhead, who has returned from military school randy as ever) but not ready to participate in man-boy orgies at the mansion of Desmond Foley (who has the job at playing the organ at funerals that might otherwise go to Nathan’s slacker father, Frank).

Nathan is very fond of Frank, mostly irritated at his mother Alma who is in charge of the household finance and neglects to pay bills just as she neglects her son, preoccupied with fortune-telling. There is a band of older youths who write for the paper of a school that includes high school and two years of college, some of whom form a theatrical troupe. Nathan is writing a play about his family that some want to mount, though Nathan’s rejection of advances from the group’s producer, Travers.

Nathan is very fond of Frank, mostly irritated at his mother Alma who is in charge of the household finance and neglects to pay bills just as she neglects her son, preoccupied with fortune-telling. There is a band of older youths who write for the paper of a school that includes high school and two years of college, some of whom form a theatrical troupe. Nathan is writing a play about his family that some want to mount, though Nathan’s rejection of advances from the group’s producer, Travers.

The most tragic character is a German refugee instructor, Kenneth Stone, whom many mistake as being a Nazi spy. Stone lost his wife and daughter and friends to the Gestapo and is plotting revenge, not cooperation. Another night-walker, he befriends Nathan. Nathan cannot save anyone from disasters, least of all himself. He is beaten up for another misunderstanding. By the end, he doubts having a vocation to write, but he is not willing to leave California and return to Minneapolis after the family house is seized for Alma’s failure to pay the property tax (and failure to be prodded by warning notices).

The book is composed of a jumble of cut-off scenes with numerous little-developed characters (Alma and Desmond being particularly caricaturish) and too many romantic and (micro-political) plots. Would that Hansen had lavished as much attention to the characters as he did to specifying the year and make of (1930s) cars! The awkwardness makes me guess that this autobiographical novel was mostly written decades earlier, languished in a drawer, and was dusted off and perhaps lightly revised by the by-then well-known septuagenarian writer (who was born in Aberdeen, South Dakota in 1923, moved from Minneapolis to southern California in 1936, and attended Pasadena City College).

I was not as disappointed by Living Upstairs, which has a a murder and a proffered solution to the whodunit question, though I’m not convinced by it. It also has way too many characters, without much characterization. That is, there are types in 1943 Hollywood.

Like Nathan Reed, Joseph Hansen grew up in the Upper Midwest, was 20 in 1943, and had difficulties getting published (until the first Dave Brandstetter novel, Fadeout, in 1970). Hansen felt he was insufficiently appreciated as a novelist (rather than as a mystery writer), though I appreciated the character of Brandstetter and didn’t much like the bleak non-detective story novels A Smile In His Lifetime (1981) and Job’s Year (1983)*. Without anything graphic, 20-year-old Nathan and his painter lover, Hoyt Stubblefield, have a lot of joyful sex and less internalized homophobia than in other Hansen non-Brandstetter novels (which did more to show questioning readers the possibility of gay life without self-hatred than did the work of New York Violet Quill writers).

Like Nathan Reed, Joseph Hansen grew up in the Upper Midwest, was 20 in 1943, and had difficulties getting published (until the first Dave Brandstetter novel, Fadeout, in 1970). Hansen felt he was insufficiently appreciated as a novelist (rather than as a mystery writer), though I appreciated the character of Brandstetter and didn’t much like the bleak non-detective story novels A Smile In His Lifetime (1981) and Job’s Year (1983)*. Without anything graphic, 20-year-old Nathan and his painter lover, Hoyt Stubblefield, have a lot of joyful sex and less internalized homophobia than in other Hansen non-Brandstetter novels (which did more to show questioning readers the possibility of gay life without self-hatred than did the work of New York Violet Quill writers).

©2018, Stephen O. Murray