I don’t believe that so-called “queer theory” explains anything at all,* after positing intracultural variability (and individual fluidity about sexual practices and identities of any sort without serious attempts to try to model either level of variability), while its predecessor, “social constructionism” failed to relate social determinants other thann a very vague “capitalism” (that failed to differentiate between capitalist and communist societies) and generally was what I long-ago [in 1995: Journal of Sex Research 32:263-265] called “discourse creationism“. Both produced some barely readable prose claiming to appeal to Theory and making gay (etc.) history in ways that are very ponderous to read about. It eeems to me that there has been a shift in publishing (beyond Duke University Press) to recover some of the lived experience of “alternative sexualities” in the past. Peter Ackroyd’s book on London (Queer City: Gay London from the Romans to the Present, 2017) signaled this change for me, and Hugh Ryan’s When Brooklyn Was Queer, (2019), as well as Jim Elledge’s The Boys of Fairy Town (2018).

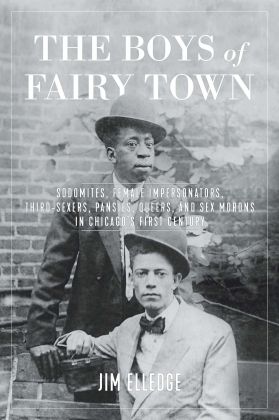

Though Elledge uses “queer” as a general term, he does not try to force historical content into the straightjacket of “queer.” The subtitle of his book is much-encompassing “Sodomite, female impersonators, third-sexers, pansies, queers, and sex morons in Chicago’s first century.” The first of these had historical primacy and, as reluctant as Michel Foucault was to recognize it, was a term for a kind of person, not just acts anyone might commit (and “sodomy” had a prototype of anal penetration, rather than being “an utterly confused cztegory,” as Foucault claimed). (BTW, compared with wht George Chauncery wrote about Gay New York (Basic Books, 1994), “pansy” and “fairy” seem to have arrived rather late to “the Second City.”

A lot of “gay studies,” certainly including my own, has focused on categories Elledge notes the categories in use, but his focus is on how people (mostly males who had sex with natal—if not necessarily masculine) lived in Chicago from 1837 until the mid-1940s. Though this long century included waves of repression connected to the world wars (both preceding and following them), there was an era in between (Prohibition with its flouting of laws) in which a public subculture flourished, particularly in the North Sides Towertown (west a mile from the Water Tower that survived the great fire), the general center of Bohemian life in Chicago (the neighborhood from which The Dial and Poetry, as well as drag shows emerged, and the duskier Bronzeville on the Near South Side (inland from Groveland Park). Although neither was a “gay ghetto,” had a concentration of norm-challenging residents.

Elledge include may photos, though I’d have liked one of performer Frankie “Half Pint Jaxon in particular. Non-Chicagoans would also have profited from at least one map of Chicago neighborhoods. I also find the system of references (some quoted words from unspecified pages within a set of entries that require then turning to the bibliography) very frustrating.

University of Chicago-trained sociologist Nels Andersen (1889-1986), who pioneered research on hoboes, identified two main types of “inverts” back during the 1920s. The dominant heterogender homosexuality involved those with “inborn” same-sex desires with “situational homosexuality” of straight-identified insertors (“trade”). It bears stressing that some of those involved in “situational homosexuality” recurrently sought out the “situation” of having male company to get them off.

Decades later, Indiana University sexologist Alfred Kinsey (1894-1956) — whose report on male sexual behavior Elledge considers formative of later organizations and reforms to a greater extent than I do — posited that there were two communities. The first was those who accepted their homosexuality, were involved in networks of friends and lovers and frequented social institutions (mostly bars and cabarets) in which homosexuals were not condemned (“group acceptance could magically transfom pariahs into human beings…. Men who lived there, among others like themselves, were able to laugh, to dance, and to love”).

The second population included men with varying degree of self-acknowledgment of their same-sex desire. Many were married and few presented themselves as “homosexual” (let alone “queer”), rationalizing their same-sex sexual behavior as a function of “liquor, cold wives, experimental urges or the like” and tended to anonymous enconters in dark places. Their same-sex sexuality was camoflauged (and, often enough, beating secretly under what Laud Humphreys would call “the breastplate of righteousness,” condemning those who did what they did, and, especially, those who serviced their forbidden desires). Members of these two populations might get together for brief sexual encounters, but did not socialize, and, at least the latter, did not cognize having anything in common (“homosexual desire”).

Elledge writes engagingly about both populations and about the rise and suppression of “pansy culture” between the world wars in a book that I think is very interesting.

* See my 2001 paper “Five reasons I don’t take “queer theory” seriously.

pp. 245-248 in Ken Plummer (ed.) Sexualities: Critical Assessments, volume 4. London: Routledge.

©2018, Stephen O. Murray