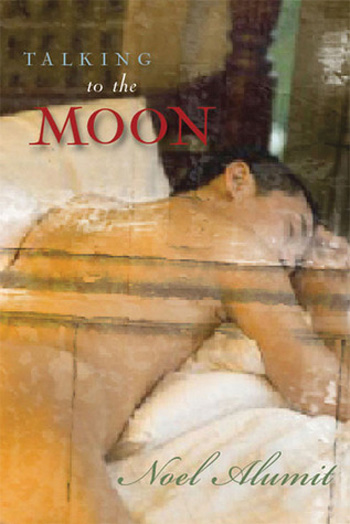

Talking to the Moon

Talking to the Moon

by Noël Alumit

Published by Carroll & Graf

Published January 3, 2007

Fiction

340 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

June 10, 2007.

What Ricardo Ramos wrote about Noël Alumit’s poignant first novel, Letters to Montgomery Clift, particularly the last point in this quotation, is highly relevant to his second novel, Talking to the Moon (2002):

Letters to Montgomery Clift begins with an eight-year-old boy cowering under a bed as his parents are beaten and his father is taken away by Marcos uniformed thugs. He eventually finds out what happened to his parents, but finding his mother again remains his primary obsession in the relative safety of Los Angeles and a sometimes comically horrifying succession of foster parents beginning with his mother’s sister. He prays—written prayers—to Montgomery Clift to sustain him and help him as he saves every dollar he can obtain to go back and search for his parents. That he writes letters to a dead idol is not quite as wacko as it sounds, though the boy whose name is changed from Bong to Bob is delusional and in forensic psychiatry lingo “a danger to himself.” Seeking the aid of dead possible protectors is a fairly normal Filipino pattern.

On the front cover of Talking to the Moon, James Ellroy (!) exclaims that it is “a terrific second novel that beats the sophomore curse hands down!” Talking to the Moon is more ambitious in that instead of having the perspective of Bob from childhood letters and present-day retrospect, it has four narrators. Moreover, Bob did not imagine Montgomery Clift replying to his letters, while two of the narrators in Talking to the Moon hear answers from the dead. Emerson Lalaban receives phone calls from his long-dead older brother Jun-Jun, who was run down by a never-found hit-and-run driver when he was 8 and Emerson 6. Their mother, Belen, receives reassurance from the Virgin Mary.

Their father an orphan who took the name Jory Lalaban was being trained to be a Catholic priest when he impregnated Belen, the sole daughter of a small provincial Philippine town’s matriarch (lumber-mill owner). Jory broke with the Holy Mother Church and undertook Igorot priesthood to the moon (which he and they regard as male, BTW). Jory is the one who talks to the moon on a regular basis. (The moon does not reply.) Jory taught Emerson some of his shamanistic role—enough for Emerson to try after Jory is shot.

The novel opens in Ellroy territory with Jory, who works as a mail carrier, being shot four times by a white supremacist who has just shot up a Jewish daycare center. This leads to a long hospitalization that drains the family’s savings.

In the first half of the book, chapters alternate interior monologues plus flashbacks by Jory, Belen, and Emerson. There is slight overlap about the present situation of the hospitalized Jory. The flashbacks proceed—across the three consciousnesses—in almost completely chronological order. This is not how consciousnesses work, but it is convenient for the reader to get the backstory in chronological order. (In Letters to Montgomery Clift, I balked at the literariness of the 8-year-old. In Talking, I think that the backstory should probably have been presented in the third-person, since it is unnaturally orderly.)

Contrary to the pop-Freudian view of gay boys (incipiently gay boys) being “mama’s boys,” Emerson and his mother before the shooting are very distant. She clearly favored Jun-Jun and without saying the words made clear that she would have preferred Emerson being the one who was killed. She considers Emerson being gay a (part of a) curse. His father is the one who tells Emerson that he loves him after Emerson comes out to his parents. And it is his father rather than his mother whom Emerson asks to teach him Ibaloi (the mother tongue of both his parents).

Emerson in the novel’s present-day (which is 1999 LA) is in his late-20s, working for a social-welfare agency. He is gay and distraught at having messed up a relationship—the longest one he has ever had—with a Taiwanese flight steward named Michael. Michael speaks pidgin English, but his interior monologues in the second half of the novel are in standard English.

Michael serves those he calls “Pearls” who fly business class across the Pacific. Michael is annoyed at himself for having fallen in love with an Asian-American with little ambition, income, or fashion sense. Adding insult to injury, Emerson would not reciprocate saying “I love you” to Michael.

Michael has been trying to wipe that man right out of his mind, but when he sees Emerson at a press conference with the mayor of LA and families of other victims of the shooter, calls Emerson, after having refused to answer 50-some calls from Emerson.

Despite his superficial/materialistic values, Michael is a very sympathetic character. He seems very Flipino to me with his label obsession and wishes to dress an American boy (even tho it is a Filipino-American one). That his only language other than very rudimentary English—English that seems to me too rudimentary for a steward flying back and forth to the U.S.—is Cantonese makes Michael seem a counterfeit Taiwanese, too. Schooled in Taiwan, Michael should speak Mandarin and Taiwanese. Some Taiwanese also speak Cantonese, but at least one other Chinese language.

Letters to Montgomery Clift included exploration of the reign of terror against dissidents of the U.S.-backed Ferdinand Marcos and Christian Right terrorism in the U.S. Talking to the Moon reaches back to Japanese occupation of the Philippines during the 1940s and shows the class divisions in the Philippines that led to the Lalabans being cursed by Belen’s dragon-lady mother.

If I’d been given the chance, I would have cut 30-40 of the 340 pages of Talking to the Moon, but contrary to what I didn’t remember of my stop-and-start reading of Letters to Montgomery Clift, I was immediately engrossed by Talking to the Moon, reading the first half in one sitting and the rest in another.

Talking to the Moon hits on many issues involving race, religion, class, homosexuality, and healthcare financing without seeming at all preachy. Alumit shows the effects on one Filipino-American family—Talking to the Moon is a “family novel.” That the surviving son is gay is important, but the book is not only about or only told by him.

The voices of the narrators are distinct and seem plausible to me. I have already expressed my view that the flashbacks are artificially orderly (as in many movies), that I have difficulty believing that Michael is Taiwanese, and that Michael is a bit cutesy. I have no difficult believing that a white supremacist targeting Jews would also shoot a Filipino who has the bad luck to be in the vicinity. I have some difficulty believing that someone shot in the line of duty as a federal government employee, whose shooting becomes part of a much publicized cause celèbre, whose wife is a nurse and whose son works the social welfare system would not receive any help with his hospital bills (or, for that matter, that she would not have long-term care insurance on him). Healthcare insurance in America is definitely full of inequities and high bureaucratic costs, but I’m pretty sure that there are funds for victims and/or that there would be fund-raising in such a case.

published on epinions, 10 June 2007

©2007, 2016, Stephen O. Murray