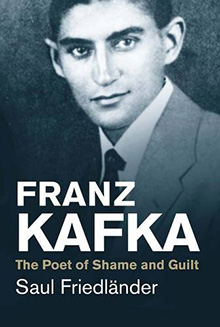

Franz Kafka: The Poet of Shame and Guilt

Franz Kafka: The Poet of Shame and Guilt

by Saul Friedländer

Published by Yale University Press

Published April 16, 2013

History (biography)

200 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com • WorldCat

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

November 23, 2013.

Though more a collection of essays on aspects of the life and writing (diaries and letters as much as stories and novel) of Franz Kafka (1883–1924), distinguished historian Saul Friedländer’s contribution to the Yale University Press “Jewish Lives” series, Franz Kafka: The Poet of Shame and Guilt, is not a biography. Nor is it an introduction comprehensible to those who have not read Kafka’s major works and/or a lot about him, though it is mostly free of academic jargon, and largely free of Freudian jargon, Oedipal as is the drama of Kafka’s psychic self-immolation.

What is occasioning consternation in some parts is Friedländer’s thesis (extending interpretations made by Mark Anderson) that Kafka’s crippling guilt and shame relate to homoerotic desires. Friedländer marshals a lot of evidence that Kafka was disgusted by female flesh but not by male flesh, about which there are some tantalizingly appreciated remarks in his diaries, made even more tantalizing by their being excised by his executor, Max Brod, when they were published. (Friedländer wonders why Brod was so sensitive to these if he were not trying to hide homoeroticism in the texts?)

Friedländer does not contend that Kafka thought about, let alone had, sex with any male, stating that it “is highly improbable that Kafka ever considered the possibility of homosexual relations.” In contrast, he thought a lot about marriage, was engaged several times, and found reason after reason to defer tying the knot, sabotaging each instance while writing of heterosexual intercourse as a “punishment” to evade.

In the famous 50-page “Letter to His Father,” an imposing and frightening giant (Father not his father small businessman Hermann), Kafka wrote:

Marrying is barred to me because it is your domain. Sometimes I imagine the map of the world spread out and you stretched diagonally across it. And I feel as if I can consider living in only those regions that are not covered by you or are not within your reach. And in keeping with the conception I have of your magnitude, these are not many and not very comforting regions—and marriage is not among them.

Kafka was plenty disgusted by his own weak body, which fit all too well with the stereotypical sissified Jewish male body conjured by anti-Semites (along with a threateningly hyper-libidinal female ones, like many of the wanton temptresses in Kafka’s fictions. Friedländer knows a great deal about anti-Semitism, not only having grown up in Prague (where he was born in 1932 into a German-speaking Jewish family that thought itself assimilated) between the world wars but as a historian of the holocaust, retired from the Club 39 Endowed Chair in Holocaust Studies at UCLA and having won a Pulitzer Prize for his book The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939–1945. The chapter in his Kafka “biographical essay[s]” attempting to sort out Kafka’s dissociation from Judaism (the religion), kabala (Hassidic mysticism), and very vague support for Zionism is especially good, cutting through a lot of literature claiming Kafka for any of them or for Catholic mysticism. (As Walter Benjamin put it, Kafka was “listening in” on the traditions but “what reached him was merely something vague.”

Friedländer’s account of Kafka’s difficulty with his Berlin publisher (Kurt Wolff) and martyrdom to writing (“I have no literary interests; I am made of literature. I am nothing else and cannot be anything else.”) is also very informative and unlikely to draw dissent from Kafka specialists. The same is true of the chapter on Kafka’s conception of being a son. I did not see much point in the extended (one eighth of the text) exegesis of the 1917 story “A Country Doctor,” (which definitely is stuffed with “blunt sexual metaphors”) and not wholly convinced of the shame and guilt being based on unacknowledged same-sex desire.

I don’t balk at and of Friedländer’s interpretation of “A Country Doctor” or of the two main novels, The Trial and The Castle. Friedländer notes that “while in each novel, the main character [Joseph K. in both] is led astray by women, in The Castle, the main epiphanies are brought about by K’s emotional or physical proximity to two males.”

Friedländer provides ample material on Kafka’s conscious and unconscious sadomasochism, which seems to me a more likely basis of the shame and guilt of which Kafka was a prophet and poet. Throw in some pederastic desires (Friedländer does). The repressed longings for male bodies seem to have been for young ones, not mature ones (age mates or elders).

23 November 2013, Stephen O. Murray