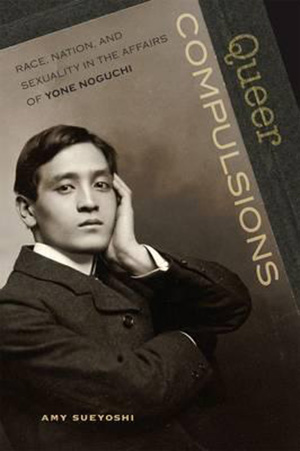

Queer Compulsions:

Queer Compulsions:

Race, Nation, and Sexuality in the Affairs of Yone Noguchi

by Amy Sueyoshi

Published by University Of Hawai’i Press

Published February 29, 2012

History (biography)

248 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

February 27, 2017

Amy Sueyoshi, the Associate Dean of the College of Ethnic Studies of San Francisco State University, has read extant correspondence between Noguchi Yone (to retain Japanese word order for names) and three American “intimates” in Queer Compulsions (published in 2012 by the University of Hawai’i Press).

The “queer” in the title primarily refers to the passionate relationship with writer Charles Warren Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard, who was less a “rice queen” than a “poi queen” (enamored to smooth brown-skinned Polynesians), though Noguchi’s relationships with two white American women were “queer” in the sense of unusual.

He was engaged to reporter (later historian) Ethel Armes for a time, while maintaining passionate friendship (or more) with Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard, and he sired a son (sculptor Noguchi Osamu) on (more than with) copyeditor Léonie Gilmour.

Noguchi’s most passionate correspondence was with Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard, with whom Noguchi also spent the most time. The least passionate correspondence, one that was almost all business (the business of editing and selling his writings) was with Gilmour, with whom he did not live, even when she took their son to Japan for about a decade—by which time he had a Japanese wife and was siring three more offspring.

The existence of Noguchi Osamu is pretty solid proof that Yone had sex with Léonie. It seems that Ethel Armes primarily loved women, and nothing Sueyoshi quotes suggests that she and Yone copulated.

There is also not explicit evidence that Yone and Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard had sex, though when Yone stayed in D.C. in Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard’s Bungalow, “they spent afternoons dozing comfortably together in a single arm chair. In the evenings they slept in the same bed.” Both wrote about loving the other and long kisses. The epistles seethe with homoeroticism, but sexual consummation is not mentioned. (Of course, when it was most likely to occur, when they were sharing a bed, they were not writing letter to each other.)

Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard was frustrated that a live-in white protégé was slipping from his grasp. His writings about Native Hawaiians he loved while in the Islands also stop short of documenting genital contact. I think that “kissing” may have been a euphemism. (Although making many surmises, Sueyoshi does not even opine about sexual consummation, so this is not her interpretation of what when on in the soap opera about which she wrote.) I wonder what Noguchi meant by “boundless” in sending Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard “boundless love and kisses” (in 1898). And the kinship lexicon of “daddy” and “boy” they employed has certainly not precluded sex in homosexual relationships a century later.

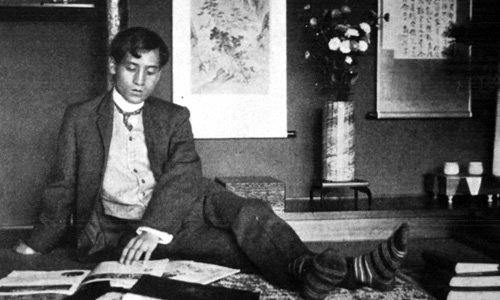

Sueyoshi quotes John Crowley’s characterization of Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard’s affairs as “pedophilic.” Noguchi Yone was not a child when he went to America, so this relationship was “androphilic.” The age discrepancy was also mapped on some gender discrepancy between the bearded older man and the smooth-skinned Noguchi, who presented himself as a “most feminine dove” to the connoisseur of smooth brown-skinned young males. Noguchi’s simultaneous courtships of white women suggested both plenty of testosterone and more than a little cunning about keeping each of the three in the dark about his other intimate engagements.

Though Noguchi was Japanese and published extensively in Japanese as well as in English, I don’t recall anything Sueyoshi quoted from Noguchi in Japanese. (I don’t know how much of his correspondence in Japanese is extant, and in the epilogue she cites some Japanese publications about Noguchi.) She lifts a word, a phrase, or (rarely) a whole sentence from correspondence in English, combining multiple sources in a single endnote, so it is not obvious which quotation is from which source.

I also find frustrating her failure to consider Noguchi’s erotic objectification of white people. She says that Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard “pursued objects rather than relationships with Japanese men” (p. 139), though (1) Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard clearly pursued an ongoing relationship with Noguchi, (2) pursued intimacy not just sexual use of his bed partners, and (3) no other Japanese man in Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard’s retinue is mentioned.

Moreover, sexual objectification in inter-racial relationships runs in both directions. (And the “compulsions” in the title is more misleading than “queer” with no one identifying his or her amorous inclinations as “queer.” Even if, as she says, she is writing about desires rather than identities, a reader of her book comes away not knowing what Noguchi’s desired sexually, or what Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard or Armes desired beyond platonic friendship.)

We already knew that strong homoerotic bonds (female-female, as well as male-male, as in “Boston marriages”) were common in the late 19th century and that a rather extravagant language of “love” occurred in 19th-century epistles. That an Asian (actually, West Pacific) man was involved in such a bond is interesting, and the daring in juggling three intimacies by one Japanese sojourner in the U.S. and the UK makes for an interesting soap opera. But this case does little to illuminate interracial erotic bonds in the first decade of the twentieth century (in the U.S., let alone in Japan). Moreover, the repetition of the same points about homosocial settings of the era seem largely irrelevant to me since the three relationships mostly were tête-à-têtes. (The text of Sueyoshi’s book is 147 pages though they seem padded be repetitions of the same points multiple times; the manuscript could have used serious editing!)

Sueyoshi does show that Noguchi Yone’s initial resistance to orientalist clichés (in an era of Japonisme) eventually gave way to trying to exploit them for economic gains (i.e., for selling his writings).

BTW, Sueyoshi makes no claims for the merits of Noguchi’s large body of work, though noting that it went out of fashion long ago. (Not that anyone today reads Noguchi’s first American patron, Joaquin Miller, either. And readers of Shttps://www.tangentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/1997/02/HICArchivesFI-1.jpgard are also rare.)

©2017, Stephen O. Murray